NAIROBI, Kenya — A damning investigation has exposed a troubling nexus between the Kenyan government and the staffing industry sending thousands of workers to the Middle East, revealing how top officials, and even the President’s family, allegedly profit while Kenyan workers face horrific abuse abroad.

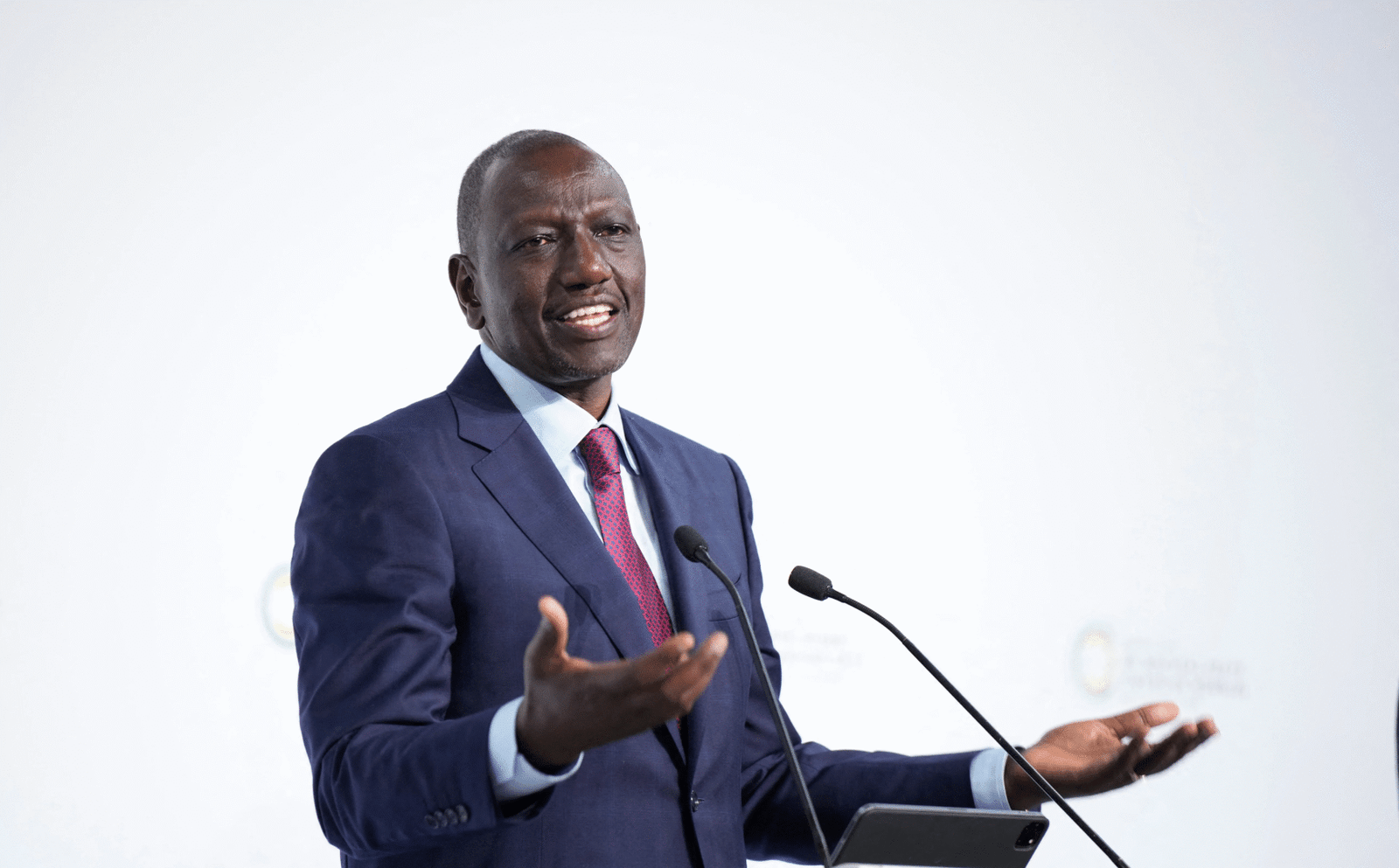

Despite mounting reports of Kenyan maids in Saudi Arabia suffering from confiscated passports, withheld wages, physical assault, and even death, the administration of President William Ruto has doubled down on exporting labor.

Instead of demanding stronger protections, the government has reportedly implemented policies that maximize profits for employment agencies, many of which are owned by politicians and their allies.

The Pan-African Image vs. Reality

President Ruto has carefully cultivated an image as a champion of the poor, a “hustler” who rose from poverty to the presidency. He frequently cites the economic importance of remittances, proudly noting they now surpass traditional exports like tea and coffee.

However, a New York Times investigation indicates that under his watch, the government effectively functions as an arm of the staffing industry.

While other nations have successfully negotiated for better wages and protections for their citizens in the Gulf, Kenya has positioned its people as some of the “cheapest, least-protected workers in the marketplace.”

Conflict of interest at the highest levels

The New York Times investigation unearthed deep conflicts of interest within the Kenyan government:

- The First Family’s stake: Records show that President Ruto’s wife and daughter are major shareholders in Africa Merchant Assurance, a key insurance provider for the staffing industry. Industry lobbyists claim the government steers recruiters to this specific company, though the firm denies receiving preferential treatment.

- Politicians as recruiters: Approximately one in 10 registered staffing companies in Kenya is owned by a current or former official or political figure. This includes the Solicitor General and the government’s top spokesman.

- Jobs for votes: The distribution of foreign jobs has become a political tool. Labour Secretary Alfred N. Mutua is accused of allocating job quotas to politicians, who then distribute them to constituents to secure loyalty.

Blaming the victims

Perhaps most shockingly, top officials have repeatedly downplayed evidence of abuse, instead shifting the blame onto the Kenyan workers themselves.

Labor Secretary Alfred Mutua, who oversees foreign labour, described Kenyan workers as having an “entitlement and attitude culture” and being insufficiently submissive.

Industry leaders echoed this sentiment. Francis Wahome, chairman of the Association of Skilled Migrant Agencies of Kenya, denied reports of women being thrown from buildings, offering a chilling alternative explanation:

“You know women,” Wahome said. “They don’t know how to calculate.”

He suggested victims fall while trying to escape using bedsheets. When asked why employers lock workers indoors, he compared the women to animals:

“You close the door for your dog,” he said. “Because it’s your property.”

Rolling back protections

In 2022, a government watchdog warned that inadequate training was a key factor facilitating the abuse of migrant workers.

Parliament considered a bill to mandate comprehensive training and punish non-compliant recruiters.

However, the Ruto administration withdrew the bill. Instead of strengthening preparation, the government cut the mandatory training period to 14 days or less to lower costs for recruitment agencies, which earn roughly $1,000 per worker.

“We want to ensure that you do a lot of business, properly and quickly,” Mr. Mutua told recruiters at a private meeting last year. “You will have a lot of money.”

A system of exploitation

The disparity in treatment is stark. A Filipino maid in Saudi Arabia earns about $400 a month and has access to rescue teams and safe houses.

In contrast, a Kenyan maid earns roughly $240 a month, a rate unchanged for seven years, and often has nowhere to turn when abuse occurs.

Hannah Njeri Ngugi, a 36-year-old mother, returned to Kenya only after activists publicized her plight. Her C-section incision had reopened while working, but her employer denied her medical care. She had received no training in Arabic or how to use modern appliances, leaving her vulnerable and unable to communicate.

Also Read: Kenya opens consulate in Jeddah to deepen ties and support Kenyans in Saudi Arabia

While the government claims to be building the nation through labour migration, critics argue it is merely feeding a high-profit industry built on the backs of vulnerable citizens.

As Senator Gloria Orwoba—who was expelled from her party after accusing the government of running a “scam”—put it:

“If this thing actually went well, I would get elected like that,” she said, snapping her fingers. But instead, she found herself fighting a system designed to silence dissent.

With the government aiming to send one million workers overseas annually, the question remains: at what cost to Kenyan lives?