NAIROBI, Kenya — For generations, the vast expanse of Lake Victoria has served as an indispensable lifeline for millions across East Africa, sustaining communities and bolstering national and regional economies.

However, its waters have increasingly become a focal point of contention, marked by frequent border arrests, seized boats, and persistent accusations of illegal fishing among the nations that share it: Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

In a significant move to de-escalate these tensions, the three East African nations are advancing a long-anticipated plan to establish a unified fishing license, a development poised to reshape governance across one of Africa’s most vital freshwater bodies.

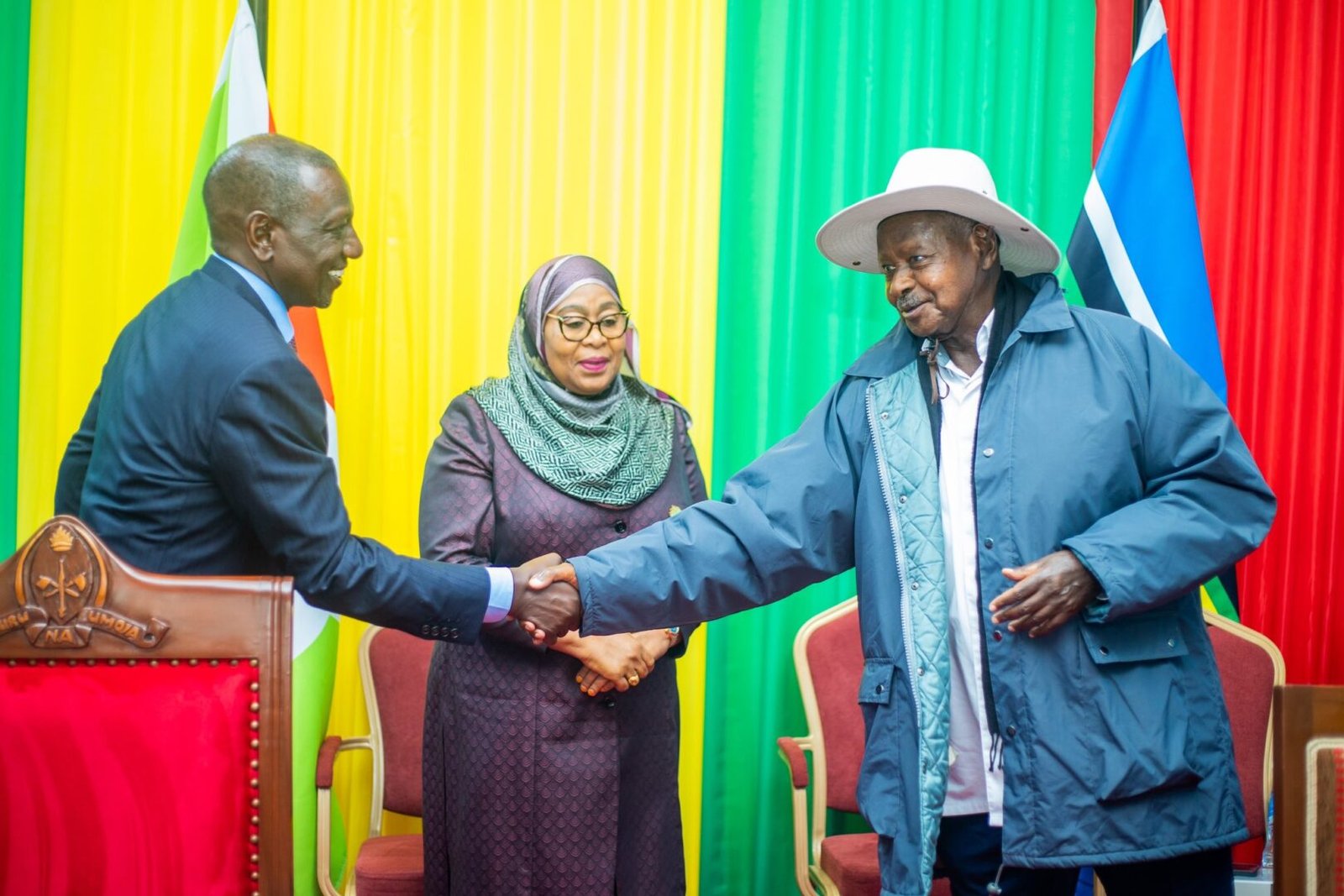

Last week, Kenyan President William Ruto disclosed that he dispatched emissaries, led by Cabinet Secretary for Mining and Blue Economy Hasan Joho, to engage Ugandan and Tanzanian officials. The objective of these high-level discussions is to definitively resolve the longstanding maritime border dispute.

“There is currently a conversation going on between our three countries so we can find a way to have a uniform license for all our fishermen, to avoid this country arresting that country’s people and the rest of what is going on at the moment,” President Ruto stated during his ongoing tour of lakeside Kenya.

A unified regulatory framework would provide fishers from all three participating countries with a single, mutually recognized permit. This proposed joint license would enable verified fishers from any of these states to access the lake freely, subject to collectively agreed-upon rules.

Furthermore, it would formalize critical monitoring and data-sharing mechanisms, empowering the three governments to more effectively track fish stocks, combat illegal fishing, and harmonize enforcement efforts.

Proponents argue that this initiative would not only alleviate cross-border tensions but also introduce much-needed order to a lake whose ecological resources are under growing pressure from overfishing, pollution, and climate change.

The ongoing discussions are also expected to address the lingering diplomatic standoff between Kenya and Uganda concerning fishing rights around Migingo Island. This enduring flashpoint, often referred to as Africa’s ‘smallest war,’ centers on a rocky outcrop in Lake Victoria.

Spanning just 2,000 square meters (0.49 acres)—smaller than a football field—Migingo Island is densely packed with corrugated metal shacks and houses approximately 500 residents, predominantly fishermen, drawn by its rich fish stocks.

In 2009, the dispute over Migingo Island nearly erupted into a violent confrontation between Ugandan and Kenyan armed forces after Ugandan police raised their flag on the island and began imposing fishing permits on Kenyan fishermen, triggering widespread diplomatic outrage.

While intermittent diplomatic negotiations have previously helped defuse flashpoints, the persistent absence of a structured policy has led to recurring disputes, with frequent arrests and detentions continuing to complicate regional relations.

Lake Victoria, recognized as the world’s second-largest freshwater lake by surface area, spans over 68,800 square kilometers and supports a basin population exceeding 40 million people. Its fishing industry is valued at an estimated $500-$800 million annually, with the prized Nile perch and tilapia dominating catches, according to the African Great Lakes Information Platform.

The lake supplies over one million tonnes of fish each year, as reported by the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation, making it central to regional food security, employment, and export revenue.

However, the benefits derived from the lake have been undermined by a fragmented patchwork of national regulations, overlapping jurisdictions, and alarmingly dwindling fish stocks.

Fishers who inadvertently or intentionally drift across invisible aquatic borders often face arrest or the confiscation of their gear. In some instances, these encounters have escalated into violence.

For example, a Ugandan fisherman operating near Kenyan waters might unknowingly or deliberately breach Kenya’s exclusive fishing zone, an act that could cost them their boat or their freedom. Local media frequently report on fishers being detained for weeks or even months, fueling rising community resentment.

“The lake doesn’t know borders,” observes Dr. Margaret Achieng, a fisheries expert based in Kisumu, Kenya. “But our governance of it has been territorial, politicised, and outdated. What we’re seeing now is a step towards rationality.” Experts are hopeful that this initiative will pave the way for a broader ecosystem management approach, moving beyond reactive policing.

Also Read: Raila Odinga urges President Ruto to resolve Kenya-Uganda Lake Victoria border dispute

Nonetheless, questions persist regarding the equitable sharing of revenue generated from license fees, the practicalities of joint enforcement, and the mechanisms that would be employed to resolve future disputes.

Past attempts at regional cooperation, such as the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project established in 1994, have yielded mixed results due to entrenched political mistrust and inconsistent implementation.

Meanwhile, fish stocks in Lake Victoria have witnessed a sharp decline over the past two decades.

Research by the National Fisheries Resources Research Institute in Uganda indicates a drastic drop in the Nile perch population in certain parts of the lake.

Overfishing, pervasive pollution, and the widespread use of illegal fishing gear have exacerbated this crisis, with economic repercussions already being felt across the region. In Kenya, data from the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) for 2024 revealed that fish export earnings plummeted by 12.07% in 2023, falling from Sh6.67 billion ($46.8 million) to Sh5.86 billion ($41.1 million).

This decline of Sh805.29 million ($5.65 million) marked the first significant downturn since 2020, when revenues decreased by Sh681.61 million ($4.78 million). Furthermore, Kenya’s fish production from Lake Victoria shrank to 70,300 tonnes in 2023, down from 86,400 tonnes in 2022, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Many stakeholders believe that the introduction of a joint license could establish a vital precedent for deeper regional integration in the management of shared natural resources.