KAMPALA, Uganda — When Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni secured yet another term in office, congratulatory messages from across East Africa arrived swiftly and predictably. Kenya’s William Ruto, Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame, Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan, and other regional leaders praised the outcome, invoking stability, democracy, and the will of the people.

What followed those endorsements was not scrutiny, accountability, or reflection—but silence.

That silence is not incidental. It is structural. And it reveals what has increasingly defined politics in East Africa: an incumbents’ alliance—informal, unspoken, but deeply entrenched, where presidents protect one another from democratic consequence.

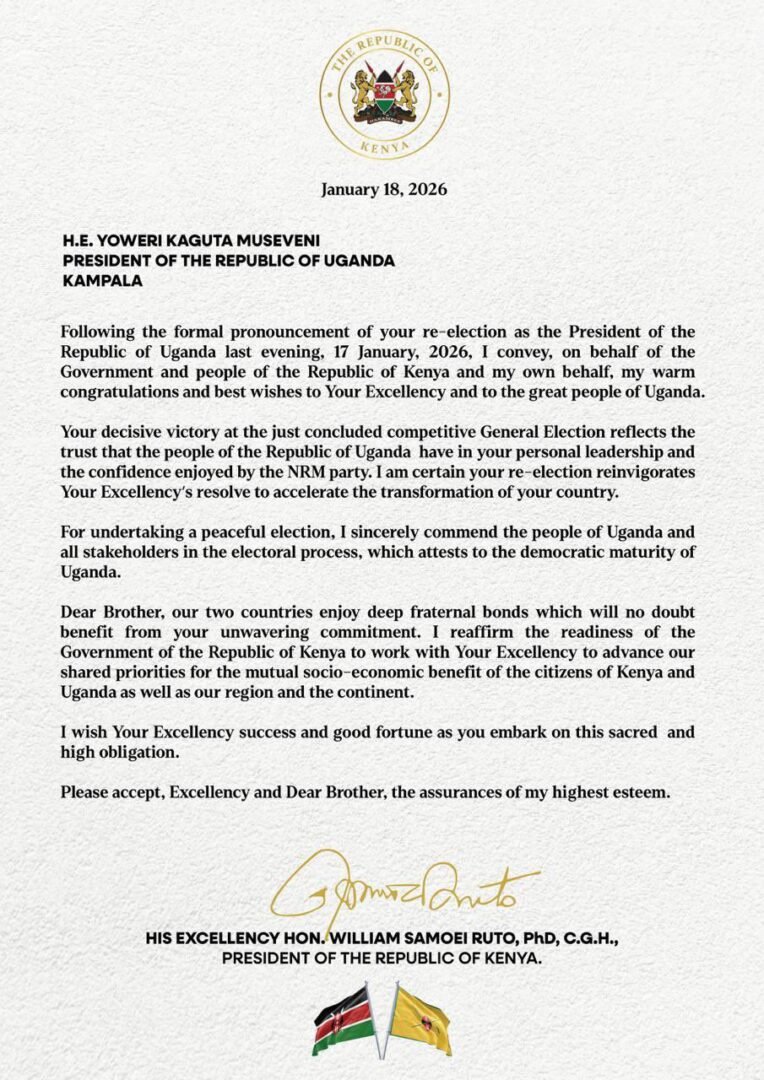

Congratulations as political insurance

In theory, post-election diplomacy is a routine exercise in regional goodwill. In practice, it has become a form of political insurance.

By endorsing Museveni’s re-election without qualification, regional leaders were not merely acknowledging Uganda’s result; they were reinforcing a shared understanding that electoral legitimacy is conferred by incumbents, not citizens.

Congratulations President Yoweri Museveni on your re-election as President of the Republic of Uganda. I extend my best wishes to you and the people of Uganda as you continue to serve your nation for the prosperity of your people. I look forward to the continued strong and productive cooperation between our two countries.”

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame has conveyed his congratulations to President-Elect Yoweri Kaguta Museveni following his re-election as President of Uganda.

The endorsements arrived despite widespread reports of election-period violence, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, media restrictions, deportations of foreign journalists, and internet shutdowns that crippled communication at critical moments.

On behalf of the Government and the People of the United Republic of Tanzania, I extend my heartfelt congratulations to Your Excellency, President-elect Yoweri Museveni on your re-election. Your victory represents the confidence and trust the people of the Republic of Uganda have in your leadership and vision. I am looking forward to continuing working with you in deepening the fraternal and historical bond between our two countries, for the benefit of all our citizens.”

Tanzania’s President Samia Suluhu Hassan has conveyed her congratulations to President-Elect Yoweri Kaguta Museveni following his re-election.

None of these issues featured prominently—if at all—in official regional responses.

A Shared Governing Script

East Africa’s political class increasingly operates from a familiar script:

- Elections must be held on schedule

- Security forces must “maintain order”

- Opposition activity must be contained

- International observers must be accommodated, but not empowered

- Results must be declared quickly

- Regional leaders must congratulate promptly

This model preserves the appearance of democracy while emptying it of contestation.

Museveni’s Uganda is often portrayed as an outlier. In reality, it represents the most mature expression of a system quietly spreading across the region, where executive power expands, legislatures weaken, courts tread carefully, and security agencies become political instruments.

The African Union’s comfortable distance

The African Union and regional bodies once again played a familiar role: observing without confronting.

Election observer missions focused on procedural mechanics while sidestepping the political climate in which the vote occurred. Statements were carefully worded to emphasise calm, restraint, and sovereignty—while avoiding meaningful commentary on abuses reported before, during, and after polling.

Also Read: From reformer to autocrat: How authoritarian regimes adapt — The case of Samia Suluhu

This posture has become routine. The AU’s reluctance to challenge sitting governments has eroded its credibility among citizens, even as it retains formal legitimacy among states.

In effect, African democracy is increasingly policed by institutions designed to protect governments, not voters.

Violence without accountability

In Uganda’s case, reports of fatalities linked to election-related security operations have not resulted in independent regional inquiries, sanctions, or diplomatic pressure.

Arbitrary arrests and abductions have been met with procedural concern, not political consequence.

Internet shutdowns, now a recurring feature of elections in the region, were framed as security measures rather than democratic violations.

The cost to journalism, business, civil society, and transparency was treated as collateral damage.

By remaining silent, regional leaders normalised these tactics.

The message is unmistakable: so long as power remains intact, the means of preserving it are negotiable.

Why Presidents Protect Presidents

The logic is self-preserving. Many of the leaders congratulating Museveni govern under systems vulnerable to the same criticisms levelled against Uganda.

To challenge Museveni meaningfully would be to legitimise external scrutiny of their own elections, security practices, and civil liberties records. Silence, therefore, becomes strategy.

This is not ideological alignment. It is mutual survival.

The cost to citizens

For ordinary East Africans, the consequences are profound.

Elections lose meaning when outcomes appear predetermined. Civic engagement declines when dissent is punished.

Trust in institutions erodes when oversight bodies look away. Political apathy grows when accountability is selective.

The incumbents’ alliance may deliver short-term stability, but it cultivates long-term fragility.

History shows that systems built on repression and managed legitimacy rarely collapse quietly. They fracture suddenly.

Beyond Uganda

Uganda’s election should not be viewed as an isolated national event. It is a regional signal, a demonstration of how power is now acquired, defended, and legitimised in East Africa.

The real question is not why Museveni was congratulated. It is why no regional leader felt compelled to condition that congratulations on justice, transparency, or accountability.

Until that changes, elections across East Africa will continue to resemble rituals of continuity rather than moments of choice.

The incumbents’ alliance may not be written down. But its effects are visible everywhere.